When You Sing the Blues, You Lose the Blues

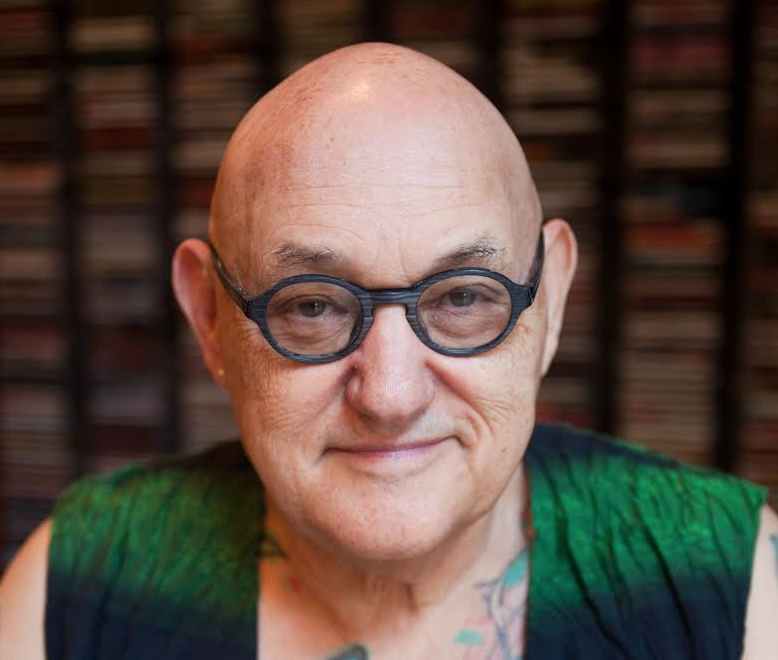

David Ritz –

I was born in 1943, and five or so years later I began to stutter.

Today I’m 70 and still stuttering.

I expect to be stuttering till the day I die.

I accept that notion. I even embrace that notion.

Over the course of my life, I’ve come to see myself as a proud stutterer. I’m proud that I’ve lived a highly successful life despite—or perhaps because of—this challenge. I’m proud that my stutter didn’t stop me from doing the things I wanted to do and saying the things I wanted to say. I’m proud that my stutter forced me to find extra fortitude. I’m proud that, as a stutterer, I have pursued my dreams. I’ve met the people I’ve wanted to meet and written the books I’ve wanted to write.

I’m proud that I have not allowed the pain that comes with stuttering—and the pain has been enormous—to hold me back. Pain was there for me as a little boy, pain as well as confusion, frustration, humiliation and shame.

I was ashamed that I couldn’t speak fluently like the other kids in my class. I was humiliated by teachers who, when they called on me and didn’t get an immediate response, presumed I didn’t know the answer when, in fact, I did. The answer was locked up in my stutter. I was frustrated when my well-intentioned parents sent me to psychologists and speech therapists with the goal of curing my stutter and the cure didn’t work. I was confused when I asked my mother and father where my stutter came from—and why I couldn’t rid myself of it—and they had no answer.

I was never told that it’s okay to stutter. In the culture of the 1950s, my parents viewed stuttering with a degree of dread. Something was wrong with their child, and they searched to find professionals who could help me achieve easy fluency.

That never happened. There are millions of early stutterers who, somewhere along the way, with or without professional help, achieve normal speech. I am not one of those. My stutter has proven tenacious through childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age. It is as much a part of me as my beating heart. I believe it is part of my soul.

Later in life I would read theories that claim the cause is biochemical and can be remedied with medication. My bias, based solely on my life experience, is otherwise. Like so many other stutterers, if I am alone in a room I can read aloud with faultless fluency. If someone enters the room, the stuttering starts. My stuttering intensifies when I find myself in uncertain circumstances; when I feel nervous or fearful or especially vulnerable; when I am asked to introduce myself; when I am tired or lonely or over-excited about expressing an idea. My stuttering, in short, is tightly tied to my emotions. It is a barometer of my feelings. If I’m relaxed—which is rare for me—I stutter less. If I’m agitated, I stutter more.

It wasn’t until high school that I began to understand that I have an excitable soul and that my stuttering is a reflection of that. I was also aware that I was likeable, and that my stutter did not impede my likeability. In fact, it gave my personality a unique flavor.

It wasn’t that I didn’t share the dream of most stutterers—to wake up one day with perfect fluency—but reason told me this wasn’t going to happen. Reason also told me that stuttering had certain benefits and even charm.

People saw and heard that I was emotionally open, even defenseless. I couldn’t cover up my nervousness. My nervousness was in my speech. When I decided not to withdraw from extracurricular activities in high school but put myself in public forums, like debate class and dramatics, I was viewed as being nervy. I was admired.

As someone who likes attention, I was adamant about not allowing my stutter to deprive me of that pleasure. In elementary school my stutter had been ridiculed, but in high school I realized there might be a way to use the humorous aspect of stuttering in my favor. As a stutterer, acknowledging humor in my speech was no easy task, especially given the pain of the past. Yet there was humor, even healing humor if I could only view humor through loving and compassionate eyes.

For example, this was a story I often shared with my friends during my senior year of high school:

After a date, I was driving my mother’s car home when I realized I was almost out of gas. It was past midnight. I pulled into a gas station. (In those days you didn’t pump your own gas.) An attendant—a big burly man in his forties—approached my car.

“H-h-h-h-h-h-h-how m-m-m-much gas you w-w-w-w-ant?”

Happy to encounter a fellow stutterer, my heart immediately went out to him. “G-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-ive me th-th-th-th-three d-d-d-d-dollars w-w-w-w-orth,” I said.

He turned beet red. “N-n-n-n-n-n-no one m-m-m-m-m-makes f-f-f-f-fun of me!” he scowled.

“I’m n-n-n-n-n-not m-m-m-m-m-making f-f-f-f-f-fun,” tried to say.

“S-s-s-s-s-s-s-stop i-i-i-i-i-imating m-m-m-me!”

“Y-y-y-y-y-y-you d-d-d-d-d-don’t understand.”

“The h-h-h-h-h-h-hell I d-d-d-d-d-don’t!”

As he grew angrier, I became more nervous and my stutter worsened. At one point I thought he would hit me. All I could do was get out of the car, look him in the eye and say, with all the energy and sincerity at my command, “L-l-l-l-look, I’m j-j-j-j-just like y-y-y-y-you. I st-st-st-st-st-stutter. R-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-really!”

It took him a few seconds to take in what I was saying. But my sincerity overwhelmed his skepticism and, much to my relief, he broke out into a smile. He stuck out his hand for me to shake. “A-a-a-a-a-ain’t that s-s-s-s-s-something,” he said. “A-a-a-a-a-in’t that some funny stuff.”

It was funny. Humor saved the day. Humor saved many of my days. Many were the moments when I could invite others to laugh with me.

The lesson I learned back in high school was that stuttering can be endearing. Roberta, my wife and soul mate of 47 years, told me my stutter was part of what initially drew her to me. It reminded her of a boy she had known in elementary school whose sweetness had touched her heart. Stuttering exposes our humanity, our vulnerability and our imperfection. All our masks are useless.

As a stutterer, it has been difficult to find the right time and context to laugh at myself. To do that has required distancing. It certainly could not have happened it my childhood. The pain was too much. But as I’ve trudged the long road of maturity, I’ve learned to use humor to lighten the load. For me, humor has lifted the otherwise oppressive seriousness that often surrounds my speech.

Yet for all my adjustments, for all my liberal use of humor and my gritty determination to go forward and have my say, the struggle has not stopped. To a degree, stuttering is a struggle—to get out the word, to find the courage to face the world with imperfect speech and deal with the emotional fallout. The struggle has dramatically decreased, but the struggle still exists.

In the mid-eighties I was in my forties when, after having written a biography of singer Marvin Gaye, my publisher asked me to go on a two-week national book tour. That meant dozens of radio and television interviews. A publicist called to see if I required media training. When she heard me stutter, she grew alarmed.

“What will happen when you’re on live TV,” she wanted to know, “and you’re asked a question and can’t get a word out?”

“I guess they’ll have to wait until I do get it out,” I said.

“Are you sure you want to do this to yourself?”

I was infuriated by her question—by the notion that presenting myself as a stutterer would harm me–and told her so.

“I’m going on the tour,” I said. “Just line up the dates and send me the schedule.”

Despite my bravado, I did experience anxiety. I’d done public speaking before, but not with this frequency and certainly not on this scale. So a couple of months before the tour, I decided to do something I hadn’t done since childhood: see a speech therapist. I was blessed to find Vivian Sheehan, whose husband Joseph had pioneered the practice of voluntary stuttering. His theory was simple: Rather than try to camouflage your stutter, broadcast it. Expose it. Early in your conversation, intentionally stutter, if only to reveal that you are, in fact, a stutterer. Thus you assuage the anxiety that comes with switching words and all the other tricks stutterers use to feign fluency. I loved the Sheehan approach: Be who you are. Be authentic.

Such affirmations have great value for me. I use them every day. Self-assertion has gotten me through countless tough times. Yet the struggle remains. It happened earlier today. I went to a large meeting where the leader asked the attendees to stand and introduce themselves by name. My heart dropped. There’s nothing that a stutterer hates more than having to say his or her name to a room full of strangers. Suddenly I was a seven-year-old, dreading the moment when the teacher called on me. For all my brave ideas about being a proud stutterer, I even considered leaving. But I couldn’t. I didn’t. Anxiously, I waited as fifteen or twenty people stood and smoothly said, “Ed” and then “Jim” and then “Mary” and then “John.” I marveled at the ease with which they spoke their names. I hated harboring a feeling I’ve had my entire life—an envy of fluent speakers.

When my turn came, I wasn’t fluent. I couldn’t say, “David.” To avoid the stutter, I didn’t start with my name. I didn’t follow the philosophy of voluntary stuttering. I thought it would be easier to get out an “M” then a “D.” It wasn’t. I said, “M-m-m-m-m-my n-n-n-n-name is D-d-d-d-d-d-david.” It was a long stutter. It was a struggle. I felt some humiliation. I felt some pride. But mostly I felt relief.

The relief didn’t last long because I soon learned that it is the practice of this meeting to pass around written material and have each attendee read a paragraph out loud. Not again! Back to grade school! Back to anxiously waiting until the sheet reaches me! Back to wishing I had the fluency of everyone else!

But I did wait. And I did read. And I did stutter. And I did survive. And I will survive when it happens the next time, and the time after that. And maybe I’ll never lose the ambivalence of being a stutterer who experiences pride one moment and humiliation the next. Fortunately, the pride is greater than the humiliation, but the humiliation is never entirely gone.

After seventy years, I still struggle not to struggle. With so much life experience, part of me feels that the struggle should be over. Part of me is embarrassed to admit that the struggle continues. Yet it does.

I’m happy to say that many times the struggle is gentle. At other times the struggle leads to self-condemnation. There remains an angry voice deep inside me that, more often than I care to admit, will say, After all this time, you still stutter! I recognize the power of that voice. It has, after all, lasted a lifetime. I can’t make it go away.

But there are other voices—compassionate and loving voices—that assure me my stutter is a perfect expression of my humanity. I want to be heard. I want to be accepted. I want to be loved. And if I’m afraid that I won’t be heard, accepted or loved, that’s exactly what my stutter is saying.

And while it is an expression of fear —a representation of fear—I’ve come to believe stuttering is also a release of that fear. Or as the great Mississippi bluesman John Lee Hooker, himself a lifelong stutterer once said, “When you sing the blues, you lose the blues.”